6 MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT TRAUMA-INFORMED EDUCATION

1. Trauma-Informed education is solely about a student’s ACE score: The ACE study conducted by Kaiser Permanente and the CDC is credited with increasing public awareness of the potential negative health outcomes of adults based on their adverse childhood experiences.

That increased awareness is good, but trauma-informed education is not solely concerned with students’ ACE score. We should use the ACE study as a catalyst to look deeper into understanding the broad scope of adversity that children are experiencing but that the study did not include. Trauma-informed education includes examining the influence and impact on students in our schools of factors such as racism (explicit, implicit, and systematic; and microaggressions) as well as poverty, peer victimization, community violence, and bullying.

2. Educators must know a student’s ACE score to successfully intervene: It is not imperative to know a child’s ACE score or specific traumatic experience to provide effective interventions. Being trauma-informed is a mindset with which educators approach all children.

Research indicates that strong, stable, and nurturing relationships foster a feeling of belonging that is essential for all students but is absolutely imperative for healing with students who have experienced trauma. Karen Treisman, a clinical psychology specialist, says, “Every interaction is an intervention.” As educators, we must understand the impact of daily positive interactions and affirmations for our students.

3. Trauma-informed education is about fixing kids: Our kids are not broken, but our systems are. Operating in a trauma-informed way does not fix children; it is aimed at fixing broken and unjust systems and structures that alienate and discard students who are marginalized.

If we view our trauma-informed approach as fixing kids, that creates a deficit mindset. Many kids are doing the best they can in the moment. We must meet all students where they are while supporting them with strong, stable, and nurturing relationships.

4. Trauma-informed educators don’t give students consequences for inappropriate behavior: There needs to be a clear understanding of the difference between consequences and punishment. Consequences by definition are designed to teach, while punishment relates to personal suffering.

It’s important to set clear boundaries and expectations and then to support students into success. When students do not meet expectations or disregard boundaries, it is imperative to teach and reteach the expectations through consistent consequences.

5. Sometimes you have to escalate a confrontation with a student to calm them down: Co-regulation is the idea of keeping calm in order to help calm a student who is experiencing anger, frustration, or fear. A dysregulated adult cannot regulate a dysregulated child. Raising our level of intensity is not a strategy that works.

We should instead use strategies that honor the student’s emotions and need for space while also getting their systems to calm in a safe way. This can be accomplished through first making sure that we really are calm and then by validating the student’s experiences and emotions in order to get to the root of what is causing those emotions.

This doesn’t mean excusing any poor choices the student may have made—it means ensuring that they’re in a state where they can understand and accept any consequences, which is necessary if they are to learn from the experience.

6. I’m a teacher, not a therapist—this isn’t my job: As educators explore the complexities of being trauma-informed, we need to remember that trauma-informed work is a journey and not a destination. It doesn’t mean that teachers need to do the work of professional therapists. Our part in helping students with trauma is focusing on relationships, just as we do with all of our students. The strong, stable, and nurturing relationships that we build with our students and families can serve as a conduit for healing and increasing resilience.

Becoming trauma-informed in our daily practice is truly a process of learning and adjustment, but it is a worthwhile process.

Taken from the article Understanding Trauma-Informed Education by Mathew Portell through the George Lucas Educational Foundation

Trauma-Informed Practices Benefit All Students

These practices can help kids build coping skills and self-efficacy—which are helpful whether they’ve experienced trauma or not.

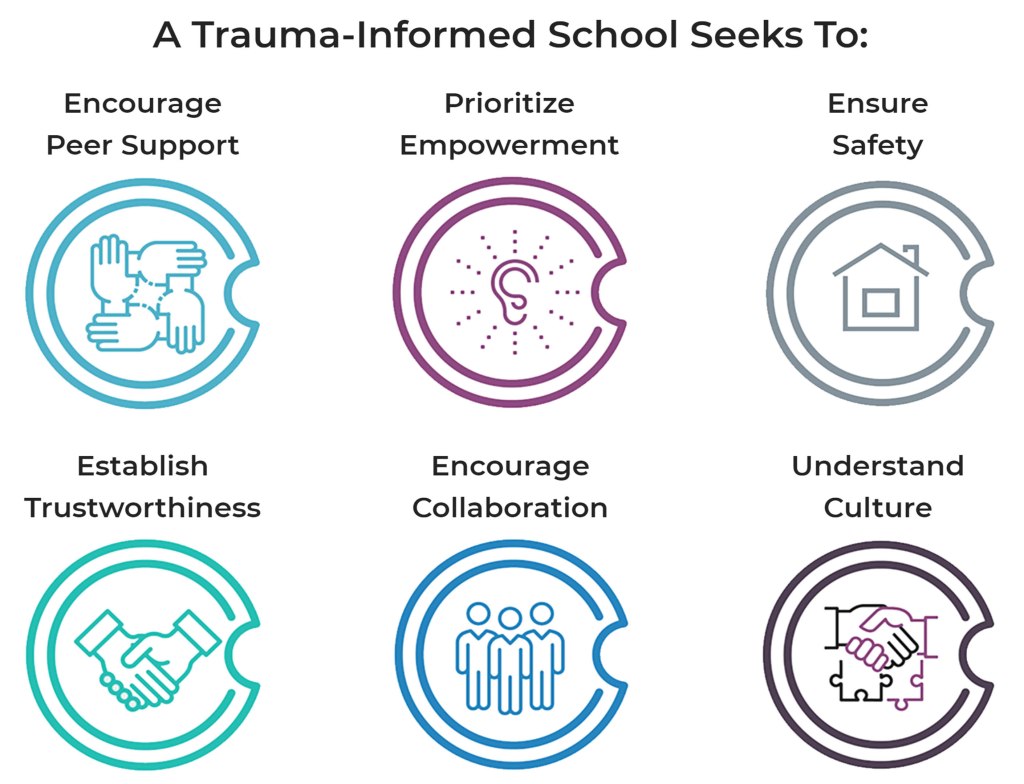

When considering implementing trauma-informed practices in your school, you might find yourself asking: How do I know which students have experienced trauma, so I can teach those students in a trauma-informed way? While it’s important to identify students in need of extra support, we can use trauma-informed practices with every single student because they benefit them all.

Think of a wheelchair-accessible ramp to a building: Not every single person needs it, but it significantly removes barriers for those who do, and signifies to everyone that the building is an accessible place. We can do the same thing for our students impacted by trauma when we remove barriers and use trauma-informed strategies as a whole school.

PROTECTIVE FACTORS

We can never know without a doubt which of our students have experienced trauma and which haven’t. Some have experienced trauma but not told anyone, or had an experience they won’t label as trauma until years later. Some students are living in traumatic situations and can’t or won’t share this for their own safety. When we use trauma-informed strategies with all students, we ensure that the students who can’t ask for support are still getting it.

Trauma-informed strategies can also help to proactively establish protective factors. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network describes protective factors such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, and coping skills as “buffer[ing] the adverse effects of trauma and its stressful aftermath.”

Some protective factors are inherent to a child’s nature or a result of early caregiving experiences, but we can teach coping mechanisms, help develop healthy self-image, and provide opportunities for practice in managing stress. Providing these supports to all students bolsters these protective factors. While not every student will experience a significant trauma in life, all of us as humans experience loss, stress, and challenges. Building up our students’ resilience will help them through these experiences.

RELATIONSHIPS

One of the most important things you can do for a child who has experienced trauma is provide a caring, safe relationship, infused with hope. Child trauma expert Bruce Perry writes, “Resilience cannot exist without hope. It is the capacity to be hopeful that carries us through challenges, disappointments, loss, and traumatic stress.” We can commit to building caring, trusting relationships with all students, relationships in which we hold hope about our students’ ability to persist and succeed.

The foundation of these relationships is unconditional positive regard for each student, the belief that every student is worthy of care and that worth is not contingent on anything—not compliance with rules, not good behavior, not academic success. When our students know we’ll care about them no matter what, they can feel safer to take risks. This risk taking in a safe environment, with support and opportunities to reflect, is one way to build resilience—in all students.

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL SKILLS

Trauma in childhood and adolescence can impact a person’s development, and these students often benefit from extra support in learning how to manage emotions in healthy ways. But learning healthy coping strategies can benefit all students, and incorporating the teaching of these strategies can be as simple as teacher modeling.

During a class in which I’m feeling overwhelmed, instead of trying to hide that, I can use it as a learning opportunity by naming it and modeling a coping strategy. “Hey everyone, I’m feeling pretty flustered because that last activity didn’t go how I thought it would. When I’m feeling flustered, it helps me to stretch for a minute. Let’s all shake it out together.”

That’s very simple, but it indicates to students that it’s normal to notice and name their own emotions. Modeling and teaching positive coping skills benefits all students by normalizing the fact that we all have tough emotions sometimes and need to use strategies to manage them.

Furthermore, if we focus on a dichotomy of “student who experienced trauma” and “student who hasn’t experienced trauma,” we lose an opportunity to expand the social-emotional toolbox of every student. Even children with no adverse experiences benefit from expanding and practicing their coping skills and strategies.

When considering whether it’s worth the time, effort, and commitment to make the cultural shifts within your own practice and your school toward becoming more trauma-informed, remember: It will all be worth it if one student can ask for or access support who thought they couldn’t before.

This information was taken from Trauma-Informed Practices Benefit All by Alex Shervin Venet