Excerpts and modified from the article “Teachers Are Anxious and Overwhelmed. They Need SEL Now More Than Ever” written by Christina Cipriano and Marc Brackett published in EdSurge.

At the end of March, the team at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, along with their colleagues at the Collaborative for Social Emotional and Academic Learning, known as CASEL, launched a survey to unpack the emotional lives of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis.

In the span of just three days, over 5,000 U.S. teachers responded to the survey. They asked them to describe, in their own words, the three most frequent emotions they felt each day.

The five most-mentioned feelings among all teachers were: anxious, fearful, worried, overwhelmed and sad. Anxiety, by far, was the most frequently mentioned emotion.

The reasons educators gave for these stress-related feelings could be divided into two buckets. The first is mostly personal, including a general fear that they or someone in their family would contract COVID-19, the new coronavirus. The second pertains to their stress around managing their own and their families’ needs while simultaneously working full-time from home and adapting to new technologies for teaching.

Once distance learning had gone into effect, we heard from one educator who shared:

“My vision of finally having someone else take care of my own kids’ education, even virtually, was smashed to smithereens. This requires 100% parent involvement, actually 200% because my kids are in two different grades!”

Given the unexpected new demands our educators are facing, we might assume that how teachers are feeling now is entirely different from the emotions they were experiencing before the pandemic. But is it?

In 2017, our center conducted a similar survey on teachers’ emotions. A national sample of over 5,000 educators answered the same questions about how they were feeling.

Back then, the top five emotions were: frustrated, overwhelmed, stressed, tired and happy. The primary source of their frustration and stress pertained to not feeling supported by their administration around challenges related to meeting all of their students’ learning needs, high-stakes testing, an ever-changing curriculum and work/life balance.

The research findings are echoed across a growing body of research on teachers’ stress and burnout.

In one study, 85 percent of teachers reported that work-life imbalance was affecting their ability to teach. Other research has shown that at least 30 percent of teachers leave the profession within their first five years of teaching. Like this research, these studies found that the general causes of teacher stress and burnout are related to a lack of strong leadership and a negative climate, as well as increased job demands, especially around testing, addressing challenging student behaviors, a lack of autonomy and decision-making power, and limited-to-no training in social and emotional learning (SEL) to support educators’ and students’ emotional needs.

So, before the pandemic, America’s teachers were already burning out. Add in new expectations of becoming distance learning experts to support uninterrupted learning for all their students and caring for the ever-evolving demands of their families, and it’s no surprise that 95 percent of the feelings they reported recently are rooted in anxiety.

We can’t control what is happening to us and around us, but we can control how we respond to it.

Emotions Matter

An anonymous teacher who filled out our most recent survey described the balancing act like this:

“There is this huge dissonance right now between the messages such as ‘be well’ and ‘take care of yourself’ at the end of emails, and ‘in this time of uncertainty.’ Yet we have to partake in multiple seminars, read links related to online instruction, legal requirements in special ed, due process, timelines, etc. Everyone needs to be reminded again about how the brain works.”

At the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, we study how emotions drive effective teaching and learning, the decisions educators make, classroom and school climate, and educator well-being. We assert that educators’ emotions matter for five primary reasons:

- Emotions matter for attention, memory and learning. Positive emotions like joy and curiosity harness attention and promote greater engagement. Emotions like anxiety and fear, especially when prolonged, disrupt concentration and interfere with thinking. Chronic stress, especially when poorly managed, can result in the persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the release of stress hormones like cortisol. Prolonged release of this and other neurochemicals impacts brain structures associated with executive functioning and memory, diminishing our ability to be effective.

- Emotions matter for decision-making. When we’re overwhelmed and feeling scared and stressed, the areas of our brains responsible for wise decision-making also can become “hijacked.” In contrast, the experience of more positive states like joy and interest tend to help people evaluate individuals, places and events more favorably compared to people experiencing more unpleasant emotions. Pleasant emotions also have been shown to enhance mental flexibility and creativity, which are key to navigating the novel and evolving demands of living through a pandemic.

- Emotions matter for relationships. How we feel and how we interpret the feelings of others sends signals for other people to either approach or avoid us. Expressing anxiety or frustration (e.g. in their facial expressions, body language, vocal tone or behavior) is likely to alienate students, which can impact students’ sense of safety in the classroom—and likely at home in a virtual learning environment—thereby having a negative influence on learning. For most students, a successful distance learning experience will require a solid partnership between teachers and families.

- Emotions matter for health and well-being. How we feel influences our bodies, including physical and mental health. Stress is associated with increased levels of cortisol, which has been shown to lead to both physical and mental health challenges, including depression and weight gain. Both the ability to regulate unpleasant emotions and the experience of more pleasant emotions have been shown to have health benefits, including fostering greater resilience during and after traumatic events.

- Emotions matter for performance. Chronic stress is linked to decreases in motivation and engagement, both of which lead to burnout. Teachers who experience burnout have poorer relationships with students and are also less likely to be positive role models for healthy self-regulation—for their students and their families.

You get the picture: When educators answer the question about how they feel at school—or, in our most recent study, as an at-home educator—we learn they spend a big part of their workday in a pretty dark place.

Teachers with more developed emotion skills tend to report less burnout and greater job satisfaction. These skills include the ability to recognize emotions accurately, understand their causes and consequences, label them precisely, express them comfortably and regulate them effectively. But the challenge is that most teachers have not received a formal education in emotion skills.

We need a greater focus on teachers’ health and well-being now, so they can thrive through this pandemic and be psychologically ready to return to school after this has passed.

Supporting Educators’ Well-Being

We know how anxious teachers (and, really, everyone else) are feeling right now. But have we thought about how we want to feel?

Previously, we asked teachers how they want to feel at school, and they’ve answered loud and clear. A few of the top hoped-for emotions were: happy, inspired, valued, supported, effective and respected.

The more sensitive we can be to our educators’ emotional needs today, the better we’ll be able to support them now and when schools reopen. The space between how we feel and how we want to feel presents an opportunity to work together to improve the emotional climate of our homes and schools. The emotional climate is the feelings and emotions a learning space evokes; that space includes both the physical one and the learning climate that is evoked through the interactions between and among educators and students. This can be applied to traditional school settings and to a virtual one.

We need to understand how our teachers want to feel, again, and then support them with what they’ll need to experience these feelings.

In the same survey we conducted at the end of March, we asked teachers to share some reflections about what they need to have greater emotional balance. Responses included time to adjust to the new normal of online learning and ways to make virtual learning fun and engaging. Teachers also expressed a strong need for honesty, respect, kindness, flexibility and patience from their school administrators. Further, they requested more realistic expectations, including boundaries around working around the clock. Among the top requests were strategies to support their own and their students’ wellness and resilience.

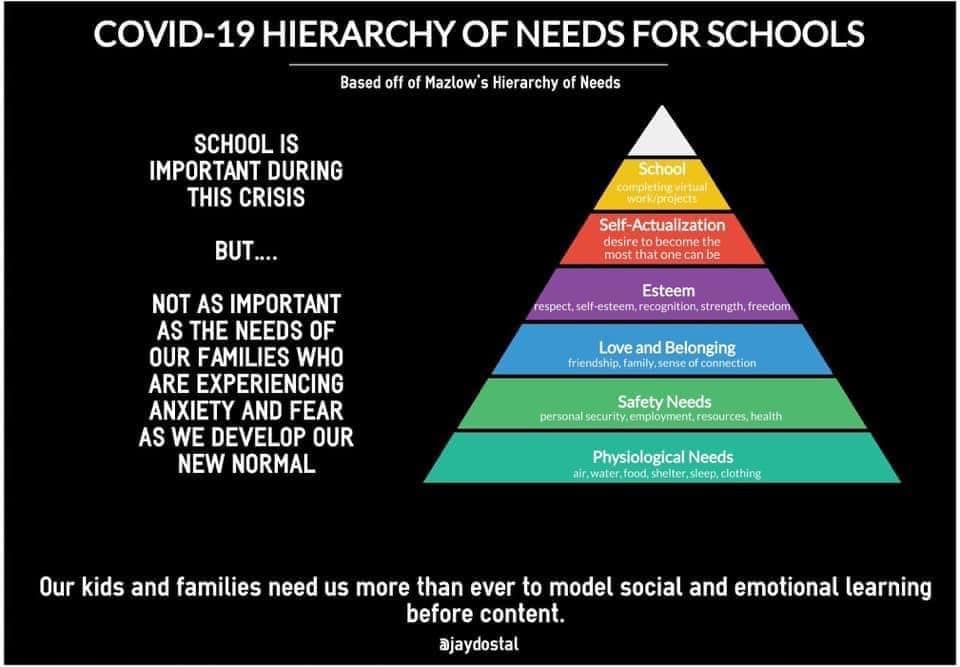

We are living through a pandemic that most of us could never have imagined. And, as we’ve shared, our educators are not in the best emotional shape. Today’s teachers, counselors and school leaders are experiencing greater anxiety, stress and burnout than ever before. If we just hope for the best, more and more educators will fall by the wayside. Fortunately, an increasing number of schools are seeing the benefits of SEL, not just for students, but for educators’ own skill development.

The time has come for all schools to address the missing link in what will help educators’ thrive—a greater focus on all adults’ health and well-being. If we want our educators to be successful—both personally and professionally—schools must be places that bring out the best in them.

The Oregon Education Association has been implementing a OEA/321 Insight Trauma-Informed Schools Webinar Series this past year. April’s session provided a practical discussion of the dimensions of regulation and how educators can help themselves by developing foundational skills in self-regulation as well as a number of other critical self-care topics.

Description: Self-Care: During this time of increased stress and uncertainty, educators are being asked to step into roles they are not prepared for. This can increase your own stress and decrease your effectiveness at a time when students need you more than ever. In addition, most educators are also providing support and care to family members and/or friends. Self-care in this time is of the utmost importance. You can listen to the entire webinar Self Care and Wellness for Educators-Building Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond, by clicking on the link below: https://www.youtube.com/watchv=jbTMBY5MEMQ&feature=youtu.be

Next week’s session is particularly relevant:

Description: Trauma-Informed Practices and Social Emotional Learning:

This session will discuss the ways in which trauma-informed practices and social and emotional learning efforts can complement each other, areas in which they overlap, and important things to consider when trying to implement both efforts. See link below if you would like to register:

http://grow.oregoned.org/events/webinar-trauma-informed-practices-and-sel